Hopscotch from home to heaven or hell and back

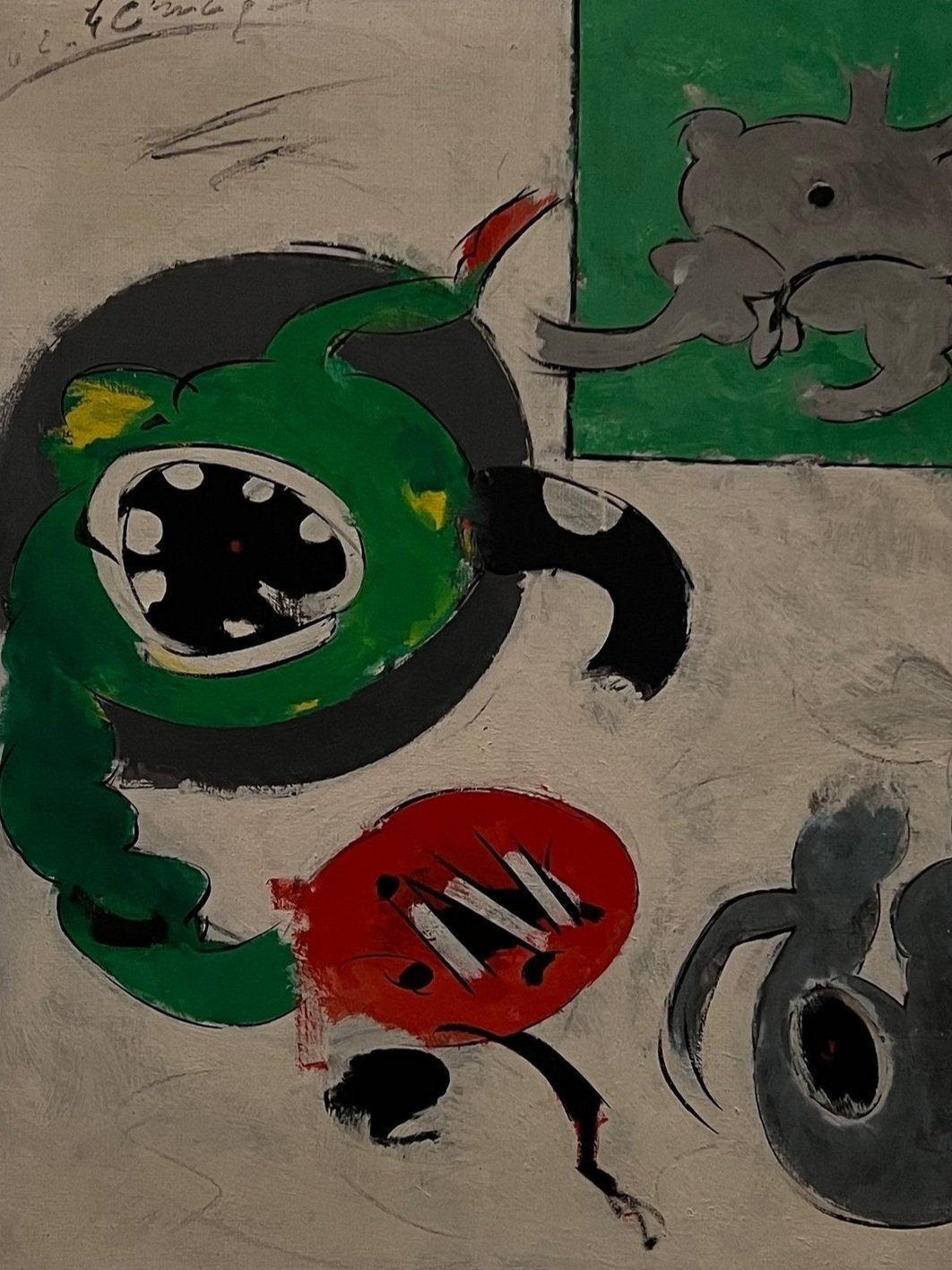

Hervé Télémaque, Portrait de famille, (Family Portrait) 1962 – 1963

I headed towards Serpentine Gallery on an actually and psychologically gloomy rainy day.

I really needed to walk around London, all these last days full of pop up news on my phone screen about new covid variants, awful racist attacks and children killings were unbearably heavy.

A walk through Hyde Park is always helpful, the colours are still intense and even when it rains the lake calms down the mind. Instant heaven.

I chose Télémaque because of the name of his exhibition, Hopscotch of the mind, intriguingly poetic and also reminding of the famous Julio Cortazar’s book Rayuela (Hopscotch).

Well, I read Rayuela a long-long time ago and the experience was really mindblowing. At that time, I wanted to think and write like that, Cortazar became my idol and obsession, reading whatever I could find of his writings and his life. I really admired his steam of consciousness writing skills, his intriguing mind, his radical political views, his poetic revolutionary vision, his whole creativity.

Rayuela is still one of my favourite books but I am in a totally different place now. I remember the passages that seduced me but I can also locate his usual sexism and although I recognize his artistic talent and literary size and that after all, he was just following the mentality of his times, I cannot but feel kind of betrayed by the fact that he was not the exception.

Anyway, last summer I read A certain Lucas and I cannot say that I didn’t enjoy it —I can still feel this combination of warmth and acuteness that I always thought that Cortazar’s writing is carrying— while Literature Class remains one of my beloved readings about writing practice.

Hervé Télémaque, an unknown to me Haitian artist went to Paris in 1961 —living and working there at the same time with Cortazar, in fact, it was during that time that Rayuela was written. A bold artist and a radical thinker, Télémaque made art utterly political, commenting on racism, imperialism and colonialism. One could assume that he could have been in the same intellectual circles as Cortazar. I would bet at least that he had read Rayuela.

His current exhibition in Serpentine Gallery is a celebration of colour and experimentation but still thoughtful and dark. Télémaque seems to have strong opinions and a broad perspective of history and politics that are continuously communicated through his creative process. His paintings are in a constant dialogue with current politico-social affairs blended with philosophical thought and psychoanalysis on the one hand, and comic imagery and neo-dada sarcasm on the other. The impact of Robert Rauschenberg’s work is more than obvious as well as Hergé’s style. His style however remains very unique and powerful.

Hervé Télémaque, Fonds d’actualité, n°1 (2002)

Most of all it is his social sensitivity that impressed me.

While in Paris and visiting an anthropology museum he show, preserved in formaldehyde jars, the body parts of Saartjie or Sarah Baartman. That may sound kind of gore but it is a fact.

Sarah Baartman had a tragic life story marked by sexism and racism that didn’t end with her death.

Her life was exceptionally narrated in the critically acclaimed movie Black Venus (2010) —where I myself learned for the first time about her. And it is such an unbelievable story that I had to search about her afterwards in order to confirm it was true. (Being surprised by certain aspects of cruelty, I’m not yet sure that it is an issue of optimism or denial.)

Mostly known as the Hottentot Venus, Baartman, a young nurse of Khoisan ancestry, was brought to Britain from South Africa at the beginning of the 19th century to be exhibited as a freak, because of her unusual —for the Western Europeans— steatopygic body type. Becoming famous because of her features she was much parodied and fetishised in satirical drawings and articles. Sadly, the barbaric racist exploitation of her didn’t stop in her exposition as a circus display, but she was also sexually abused, prostituted and finally died of a sexually transmitted disease. She was just 25 years old. And it didn’t stop there.

Her exploitation went on after her death. Her body parts were kept as exhibits of her body type, firstly in the Muséum d'histoire naturelle d’Angers and then in the Musée de l’Homme, where Télémaque came across them. From the moment he found out about her story he decided that every one of his female models will look like her.

In his painting Vénus hottentote, (Hottentot Venus) (1962) thus, it is the feeling of his very first encounter with her in such a freakish way that is expressed. In this abstract artwork, his choice of grey, red and green of the undefinable body parts and this impression of flowing create a sense of pain and repulsion, a repulsion towards a society that permits acts like this. The knowledge that the image is about a person in pieces is strong enough even before you realise that the human pieces were exposed in a museum. The monstrosity of the colonial world is given here explicitly. And the artist’s use of his pop-expressionistic abstract idiom is absolutely functional.

Hervé Télémaque, Vénus hottentote, (Hottentot Venus), 1962

In 1978, Diana Ferrus, a South African poet of also Khoisan ancestry wrote the poem I’ve come to take you home as a tribute to Sarah Baartman and as a voice for releasing Baartman’s remains from the museum and bringing them back to her country. There was a whole movement about this and it eventually happened after Mandela’s formal request to France in 2002 —though not without legal debates (imagine!).

Ferrus’ lyrical but strong poem had a decisive impact on the final decision.

“I have come to wrench you away,

away from the poking eyes of the man-made monster

who lives in the dark with his clutches of imperialism

who dissects your body bit by bit,

who likens your soul to that of Satan

and declares himself the ultimate God!

(…)

I have come to take you home

where the ancient mountains shout your name.

I have made your bed at the foot of the hill.

Your blankets are covered in buchu and mint.

The proteas stand in yellow and white—”

Baartman today is finally at peace, buried home.

Getting back home from the park-heaven I was thinking obsessively about hopscotch, as when walking in parks I bump often into chalk traces of the game. This time washed out by the pouring rain.

The square at the middle of the hopscotch route, the one you stop before getting back (to earth or home) is usually named heaven. Is maybe hopscotch an existentialism’s life metaphor as an unstoppable up and down where heaven can also be hell while when heaven is always brief? Sarah Baartman got to a permanent hell that took so long before getting back home. Longer than a life. And why the hell hopscotch is supposed to be forbidden in Buddhism? A culture whose prophet got up to satori and then came down to help the rest of the people get it? And if according to Kant art is the playful act the mind needs to get relaxed, creative and trained for its long and difficult trip to cognition, couldn't art also be considered as the hopscotch of the mind?

In any case, great art has this undeniable power of creating brainstormings, leading you unstoppably from earth to heaven or hell and back, from actual facts, everyday life and politics to fictional stories, fairy tales and mythology and back to history, society and reality, interrelated, combined and in dialogue, and —as reality is usually the hell point—, criticizing and commenting on social inequality, racism, sexism and colonial policies, exactly as Cortasar’s literature, Ferrus’ poetry and Télémaque’s extraordinary painting.