My curious meetings with Hildegard of Bingen

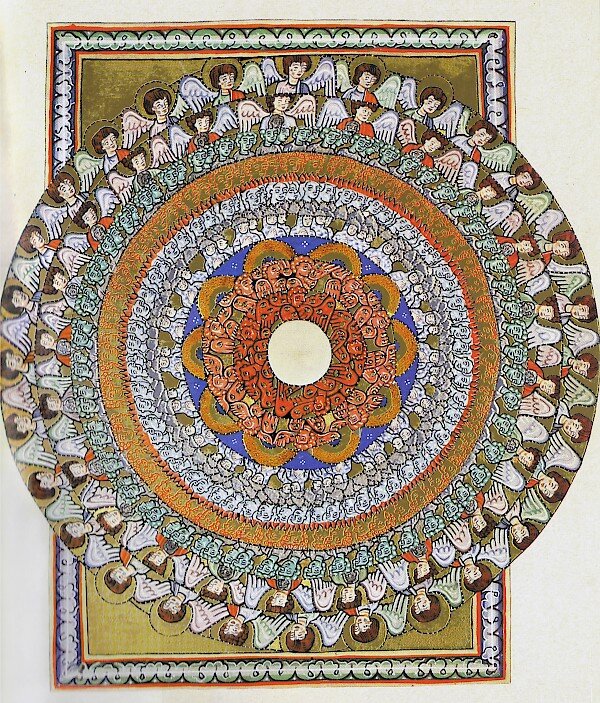

Hildegard of Bingen-The choirs of angels

I love coincidences.

In fact, I think that through coincidences the universe tries to disclosure some of its functions.

Chance is a fertile idea. Without chance, there would be no evolution. According to Lucretius the swerve —the random movement of the particle that makes it diverge from its straight itinerary and meet with another one— gives birth to possibility; it is this meeting that produces the new.

Chance has many ways of expressing its power in our everyday life. And sometimes make you doubt its existence.

Anyway, when coincidences are harmless they are an exciting aspect of life and I love trying to de-codify even if there is no code to be broken.

I met Hildegard of Bingen for the first time in the exhibition The Botanical Mind in Camden Art Center some months ago, an exceptional exhibition coping with the very unique subject of plants’ intelligence and how human beings by isolating themselves in their imaginary centre of the universe, ignored nature’s ways of communication and their poetics.

The exhibition contained some of Bingen’s drawings related to her theology and botanical researches.

Hildegard of Bingen lived in the 12th century and was a nun and a lot of other things. She was a mystic but also a writer and a composer, a scientist and a philosopher, a polymath and an early ecologist. Because of her monistic worldview, she had vast respect for nature, which she studied with reverence. Among other things, she wrote theological and botanological works and she invented a language (Lingua Ignota). In her writings microcosm and macrocosm have the same structure, studying one means you can understand the other while organic life and flora apart from a language have also their own manner to express spirituality. Thus of Bingen has an idiomorphic religious approach to nature as one more expression of god.

Wednesday evening I got back to Hildegard of Bingen and her beautiful natural philosophy considering writing an article about her. Thursday morning I had booked a time slot to visit a small gallery in Soho, Amanda Wilkinson Gallery where the first solo show of Richard Porter, an artist I didn’t know, is presented.

I love Amanda Wilkinson gallery. First of all, it is very well hidden on a Soho floor (the first time I had visited I had to ask around to find it, citymapper was incapable to locate it). Secondly, it has some very special and different artists to present.

I had seen this work that accompanies his press release.

Richard Porter, Metamorphosis (2020)

There is something tender and sad in this image. Something terrible seems to have happened. The empty nest and the stars reminded me of the Gaza bombardment, a video of the falling bombs that my husband showed me a couple of days ago, asking me to guess what it was. Not fireworks but bombs. Terror.

While going to the gallery, in the empty Picadilly line, I was reading a book I recently started while researching another woman natural philosopher of the past —some centuries later than Hildegard of Bingen— Margaret Cavendish. Cavendish, a rich Duchess who lived in 17th century’s England, was a materialist philosopher, a writer and a poet. She also wrote one of the first science-fiction books named The Blazing World.

As expected the strictly patriarchal environment of her era didn’t welcome her writings. The Duchess was ruthlessly mocked and laughed at and her bold writings were considered useless. However, in the last decades, her work has been re-discovered and there is even a Scientific Community dedicated to her thinking.

In 2014, Siri Hustvedt, a contemporary writer and neuroscientist, inspired by Cavendish life and condition wrote a novel borrowing Cavendish’s novel name, The Blazing World. The book talks about a talented and polymath woman artist who, trying to introduce her work to a large audience, “borrows” the identity of male artists.

Why I write all these? To end up to my second meeting with Hildegard of Bingen in the pages of Hustvedt’s Blazing World. Her heroine, Harriet Burden, studies of Bingen among other things. (Small coincidences that make you smile in the underground behind your mask).

Well, I can make my links between all these fantastic women. (Of Bingen for example was the 8th child of her family just as Cavendish was, while both in their heterogeneous writings that encompass a kind of materialistic philosophy and extended theology, use often dialogues to articulate their thesis. Plus they were both polymaths and artists —of Bingen writing music, Cavendish writing literature and poetry - just like Hustvedt and her Harriet.)

Arriving at Porter’s exhibition, the feeling I had when I first looked at the press release painting kept occupying me. The one accompanying a human tragedy; could be AIDS, Covid 19 or bombing Gaza. The sadness towards innocent victims and cruel governments.

Small dead birds laying on ruins or medicine boxes. Small, awkward tombs, memorials to the ones who left and the ones who were capable of their death. Candles, tender creatures, bones and ruins. And some vast emptiness in the paintings - the whole sensation felt like Gonzales-Torres art. Beautiful and urgent.

Asking about the artist and the books I saw around in the gallery —Richard Porter has founded a small press named Pilot Press publishing queer poetry— the gallerist told me about a small bookstore where I could find his books. So, although it was pouring with rain I continued my strolling towards Cecil Court where the Tenderbooks is.

Tenderbooks is a small oasis in the bookstore field of London. In its fantastic collection of independent publishing, I almost forgot what I was searching for. While leaving the place, with an anthology of queer poetry about healing and a Lyn Hejinian volume of essays, I spotted a small purple book with some beloved names on its cover: Ursula K. Le Guin and Donna Haraway. The carrier bag theory of fiction is a small essay by Ursula K. Le Guin prologued by another small essay by Donna Haraway with (bonus!) images by Lee Bul.

The book (that I started browsing through in the underground) was published in 2019 as the first book of a small brand new publishing house named Ignota “in a shared intention to formulate an experiment in the techniques of awakening under the sign of Hildegard of Bingen’s mystical Lingua Ignota” says Haraway in her Preface.

And that was my third meeting with Hildegard of Bingen.

As I regard my life as a small wave in the vast ocean of life I’d like to end with an oceanic song borrowed from this extraordinary playlist.