Muse of Anarchy

A survey in the Eileen Agar's art and life with the occasion of her retrospective in Whitechapel Gallery, London

In 1939 Eileen Agar (1899-1991) made a bold cubistic painting, full of her characteristic colours and patterns. She initially planned to name it "The Urn Goddess" because of the ample amphora-shaped body in the centre of it. After some consideration, though, she ended up to the title: "The Muse of Construction", a reference to the numerous paintings on the artist's muse, mainly implying the usual female inspiration of the male creator.

In the case of Agar, however, the muse was not a woman but a man, specifically the most famous artist of her times (if not of the whole contemporary art history) and the one with the most "muses" in his work: Pablo Picasso.

That was not an easy or light decision. Agar, already a mature artist and a fairly recognised one (compared to other women artists of her time), had photographed Picasso on the beach on the French Riviera in Mougins, Alpes-Maritimes, where the artist lived with his lover (and muse), the painter and exceptional photographer Dora Maar. The famous couple regularly invited friends to congregate. Agar and her husband-to-be Joseph Bard spent their holidays there, all together with some other eminent art personalities and their muses: the art historian and artist Roland Penrose with the photographer Lee Miller, Man Ray and Paul Eluard with his wife, Nusch Eluard.

Agar was fed up with the patriarchal principles of the surrealist circles where, as she characteristically writes in her autobiography, sexual freedom was attributed only to men while women were just reduced to the role of the muse. Being in this surrounding dense masculinity and sensing Picasso's strong mental influence, she decided to reverse the roles and "use" controversially and mischievously the famous A-male as her, rather heavyset, male muse.

That was an act much illustrative of Agar's whole emancipatory path in the art world and especially in the rugged --for a woman-- fields of Surrealism and Cubism. From her early age, she was a creature independent and free, ready to abolish any set rules for her, either these considered family or art.

Born in Argentina in a very wealthy but utterly conservative British family, Eileen felt since a very young age her artistic inclination and had the nerve to follow it despite her parents' conventional plans about her (involving mainly a good marriage and family).

She managed to get into the prestigious Slade School of Art. Very soon, she had left the family home, travelled around Europe and reached inside the most famous artistic circles of her times, taking part in several major international exhibitions. And what's more, her art wasn't going to remain confined to any rules, academic or not. Having an acute sensibility of modernism's radical waves that were changing western art in the middle of the 20th century, she managed to balance knowledge and insight into a very personal artistic language.

Agar's art is beautiful, playful, and unexpected. Her unique artistic idiom resulted from a broad study, hard work and experimentation in combination with her tremendous talent. She used her influences and multiple inspiration sources with such incredible freedom that she went beyond the existing movements of her times. Although she had occasionally been characterised as a cubist, a surrealist, or an abstract artist, she never accepted any label.

During her almost 80 years' career, Agar experimented with several media and created paintings, woodcuts, collages, assemblages, sculptures, and photographs. There are some basic elements, though, that cross the whole of her work: A strong sense of colour, a unique and narrative rhythm, an attraction towards embryonic and organic shapes and an elegant balance between abstraction and surrealistic mysticism.

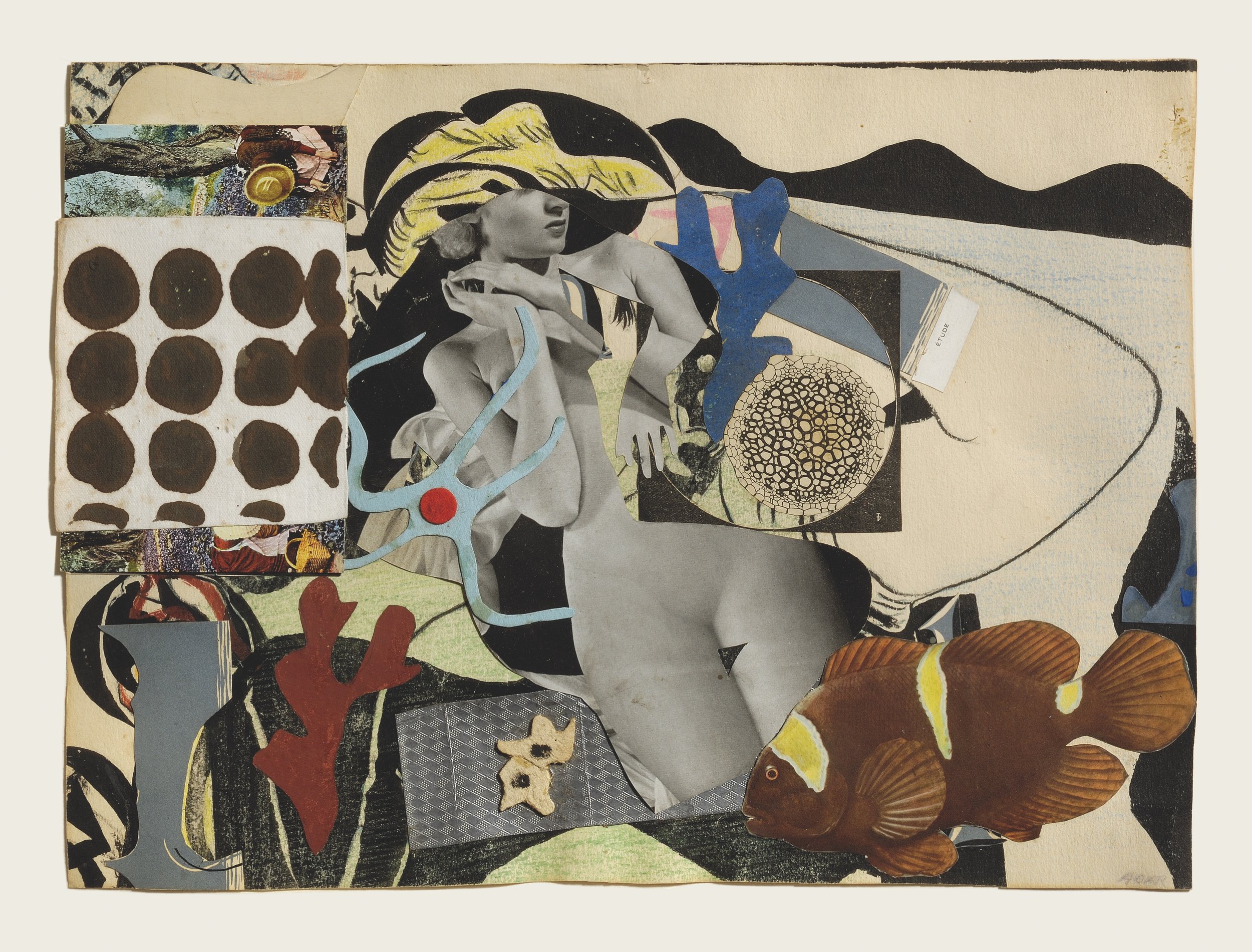

All these elements can clearly be noticed in some iconic works of hers, like the large mystical painting "Autobiography of an embryo" (1933-34), a tender ceremonial contemplation about birth and life, or the sensual collage "Erotic Landscape" (1942). The latter, a phantasmagory of organic shapes implying marine landscapes around a female body, made during World War II, seems like a desperate seeking of visual pleasure and beauty as an anchor through war's disasters. Agar and Bard during war were politicised and voluntarily engaged in social serving. All this period, although devastated and worried about the war calamities, she kept creating works manifesting turbulence but hope as well. In her glorious "Dance of peace" (1945), made just after the end of the war, the joy and optimism for a new beginning are combined with sensuality and her love of nature. Its distinctive realisation is inspired by the collage techniques that had given her so much new expressive freedom in previous works.

Although collecting strange objects had always been a way of activating her imagination --a par excellence surrealistic method of inspiration--, after she met with the British painter Paul Nash in 1935, she begun using found objects, mainly organic, in her collages and assemblages. Her sculptures after this meeting -- which was pretty productive for both artists who were in close collaboration until Nash's death-- became small cabinets de curiosities --like the playful "Untitled" (box)(1935)-- or mysterious complex syntheses like the dreamy "Marine Object" (1939).

In the retrospective exhibition in Whitechapel Gallery "Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy", the extraordinary life and career of Eileen Agar are presented through her most famous works but also some rare ones. Two well-known, powerful sculptures, "Angel of Mercy" (1934) and "Angel of Anarchy" (1936-37), dominate the ground gallery with their bold and impressive technique. Here, Agar declares her two primary impulses dynamically: anarchic rigour for political change and tender mercifulness towards humankind.

Still, some lesser-known and smaller works are also distinctive. I singled out two. Firstly, a small and sensitive self-portrait named "Eileen looking out" (1935) where the artist is gazing happily at her future holding a pallet. Despite its simplicity, there are some fine drawing qualities and a sophisticated game between similar shapes and primary colours.

Secondly, a peculiar sculpture of her later years, "The Fish Basket" (1965), composed of a head-shaped basket with two shells and a cardboard-made shrimp inside. The spirited synthesis reminds me of Kiki de Montparnasse's inclined head in the famous Man Ray's "Black and White" (1926).

Brave, intelligent, and playful, Eileen Agar kept making art till her death in 1991, after having traversed almost the whole of the 20th century. Her fascinating and complex artworks, indicative of the female emancipated mid-century genius, are full of secrets, stories and enigmas, yet to be discovered by an enthusiastic and imaginative audience.

London, 2021

this text was published in the art website artzine the spring of 2021